295 pages

English language

Published March 8, 1980 by Knopf : distributed by Random House.

295 pages

English language

Published March 8, 1980 by Knopf : distributed by Random House.

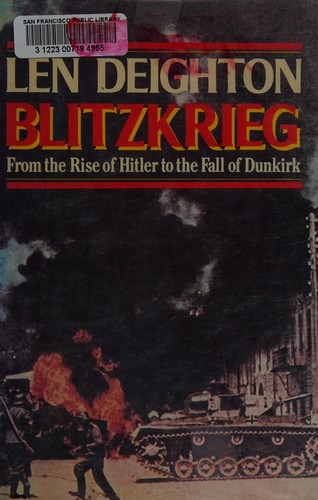

Deighton, author of SS-GB and other thrillers, turns to history again with this companion piece to his own, more dramatic Fighter (1977). Paralleling that chronicle of the Battle of Britain, Blitzkrieg works its way from Germany's defeat in 1918 to the application of ""lightning war"" strategy in the opening rounds of World War II. At first glance, there seems to be little new here, almost nothing that couldn't be gleaned from reading William Shirer. One possibility, however, is to take this as a warning: the debacle on the Continent in May 1940 resulted more from the psychological unpreparedness of the Allies than from the genius of Hitler's Blitzkrieg specialist, Heinz Guderian. Deighton repeats what we already know--that the Allies were actually stronger in terms of armor than the Germans, but had been trained for slow-motion, set-piece battles. This ""Maginot Line complex"" prevented the French and English from concentrating forces rapidly …

Deighton, author of SS-GB and other thrillers, turns to history again with this companion piece to his own, more dramatic Fighter (1977). Paralleling that chronicle of the Battle of Britain, Blitzkrieg works its way from Germany's defeat in 1918 to the application of ""lightning war"" strategy in the opening rounds of World War II. At first glance, there seems to be little new here, almost nothing that couldn't be gleaned from reading William Shirer. One possibility, however, is to take this as a warning: the debacle on the Continent in May 1940 resulted more from the psychological unpreparedness of the Allies than from the genius of Hitler's Blitzkrieg specialist, Heinz Guderian. Deighton repeats what we already know--that the Allies were actually stronger in terms of armor than the Germans, but had been trained for slow-motion, set-piece battles. This ""Maginot Line complex"" prevented the French and English from concentrating forces rapidly enough to blunt German thrusts in the Ardennes and, later, at Sedan. Deighton writes that Guderian, ""whose knowledge of mechanized warfare exceeded that of any man in the world,"" had welded the Wehrmacht into a highly mobile force that could advance as fast as its combat engineers could replace demolished bridges; that the ""Creator of the Blitzkrieg"" trained his men in forced route marches and then used only his most seasoned troops against the Western Allies; finally, that the Luftwaffe (under the command of Goering) provided a constant air umbrella for the swift-moving panzer columns. ""The defeat of the Allies on the Continent in 1940 was a failure of communication and command,"" the author concludes. Irony of ironies, Guderian's opening rounds could have ended the fight for England, but Hitler threw away the fruits of this incredible upset win by letting the 300,000-man British Expeditionary Force escape at Dunkirk. There is little evidence of original research here, and less of the Deighton snap than usual; but the conjunction of his name and today's crises probably won't make an audience hard to scare up.