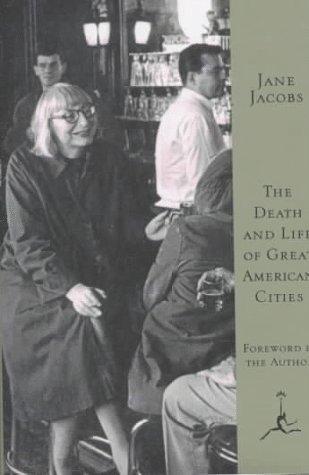

Umpteenth read. Always worth a revisit.

User Profile

"Why, yes, I am still upset that the Library of Alexandria burnt down"

This link opens in a pop-up window

Murf's books

2025 Reading Goal

83% complete! Murf has read 20 of 24 books.

User Activity

RSS feed Back

Murf wants to read Freedom by Angela Merkel

Murf finished reading The Wages of Destruction by Adam Tooze

Murf finished reading Hogfather by Terry Pratchett

Hogfather by Terry Pratchett

Hogfather is the 20th Discworld novel by Terry Pratchett, and a 1997 British Fantasy Award nominee. It was first released …

Murf started reading Hogfather by Terry Pratchett

Hogfather by Terry Pratchett

Hogfather is the 20th Discworld novel by Terry Pratchett, and a 1997 British Fantasy Award nominee. It was first released …

Murf finished reading Douglas Adams's Starship Titanic : a novel by Terry Jones

Murf started reading Douglas Adams's Starship Titanic : a novel by Terry Jones

The intro is hilarious - 'Terry is one of the most famous people in the known universe, and his bottom is only slightly less well known than his face. It has, of course, only been displayed when strictly necessary on artistic grounds, but such is the nature of his art that this has turned out to be extraordinarily often.'

Got this on paperback years ago, it's a fun, quick read.

Murf finished reading Berlin by Antony Beevor

Murf started reading Britain's War: Into Battle by Daniel Todman (Britain's War, #1)

Britain's War: Into Battle by Daniel Todman (Britain's War, #1)

Great Britain's refusal to yield to Nazi Germany in the Second World War remains one of the greatest survival stories …

Murf started reading Berlin by Antony Beevor

Berlin by Antony Beevor

Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (also known as The Fall of Berlin 1945 in the US) is a narrative history by …

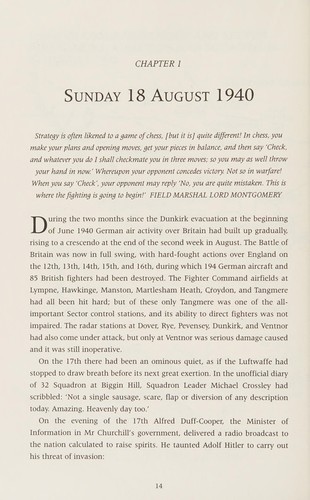

Murf rated The hardest day: 5 stars

Murf finished reading The hardest day by Alfred Price

Murf started reading The hardest day by Alfred Price

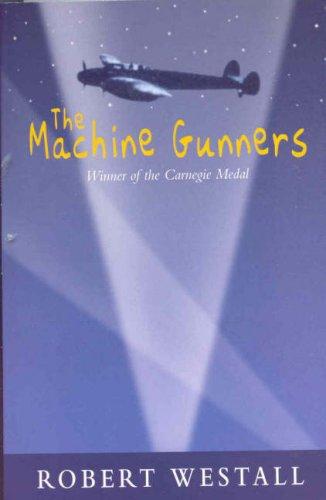

Murf finished reading The Machine Gunners by Robert Westall

Murf started reading The Machine Gunners by Robert Westall

The Machine Gunners by Robert Westall

After an air raid, a group of English children find a German machine gun and hide it from adults who …