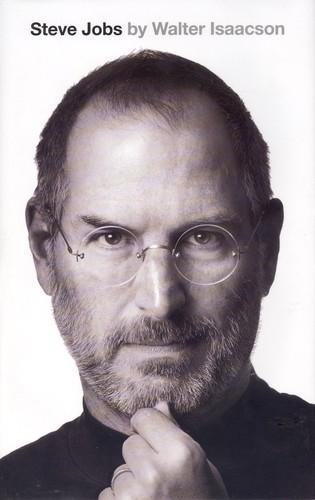

Absorbing from start to finish, a riveting read full of fascinating details.

User Profile

"Why, yes, I am still upset that the Library of Alexandria burnt down"

This link opens in a pop-up window

Murf's books

2025 Reading Goal

83% complete! Murf has read 20 of 24 books.

User Activity

RSS feed Back

Murf started reading Nemesis by Max Hastings

Nemesis by Max Hastings

A masterly narrative history of the climactic battles of the Second World War, and companion volume to his bestselling 'Armageddon', …

Murf finished reading Abyss: The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962 by Max Hastings

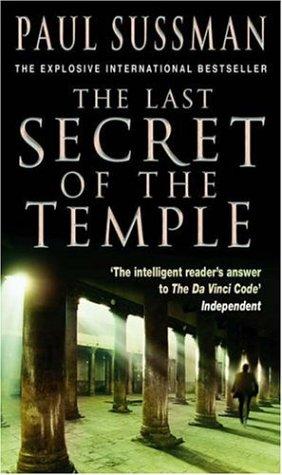

Murf rated The Last Secret of the Temple: 5 stars

The Last Secret of the Temple by Paul Sussman

Pushing the Dan Brown buttons - a rip-roaring, edge-of-your-seat adventure thriller.Jerusalem, 70 AD. As the legions of Rome besiege the …

Murf started reading Abyss: The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962 by Max Hastings

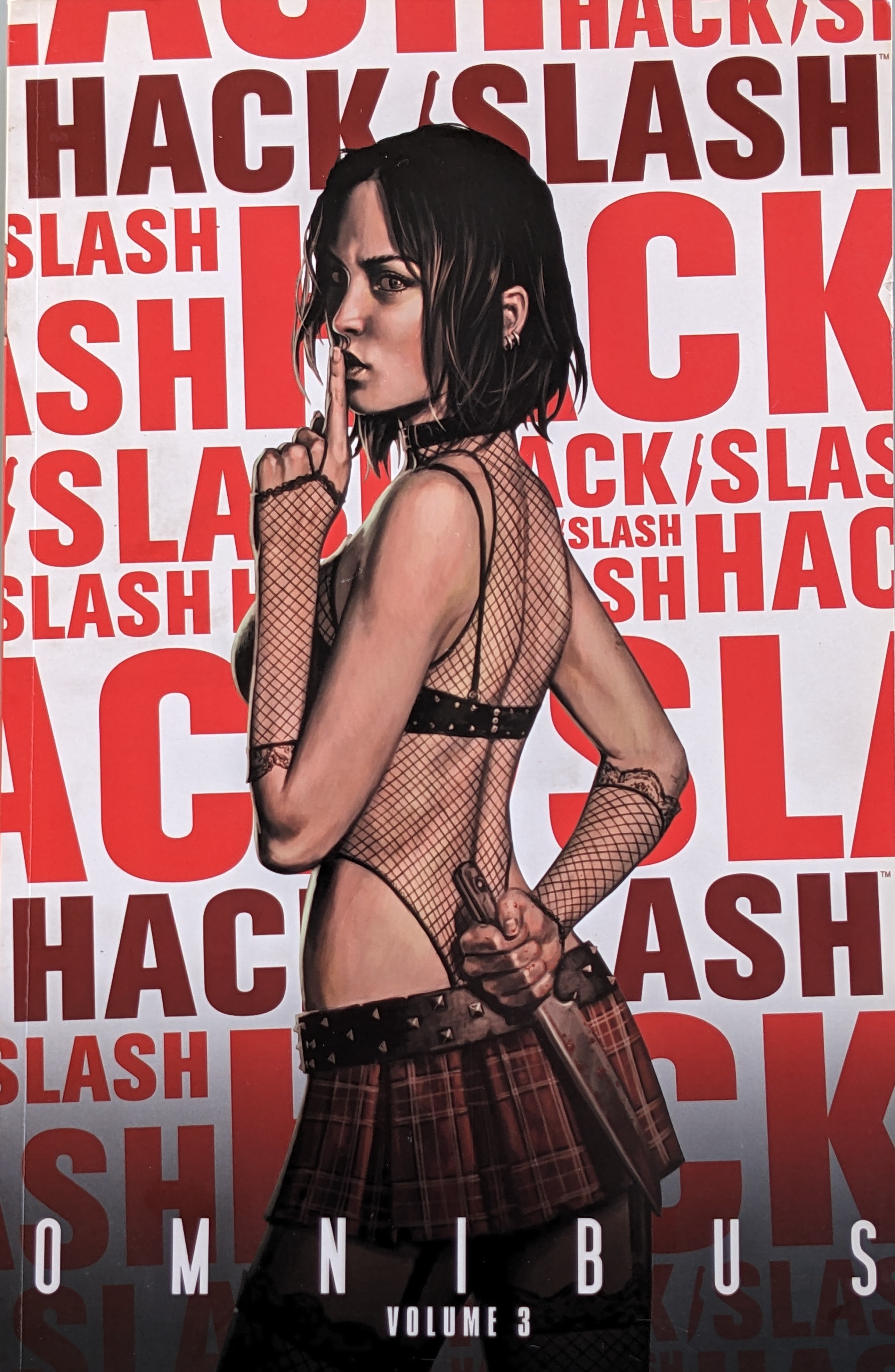

Murf finished reading Hack/Slash Omnibus Vol. 4 by Tim Seeley (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #4)

Hack/Slash Omnibus Vol. 4 by Tim Seeley, Kevin Mellon, Ryan Ottley, and 1 other (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #4)

Murf started reading Hack/Slash Omnibus Vol. 4 by Tim Seeley (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #4)

Hack/Slash Omnibus Vol. 4 by Tim Seeley, Kevin Mellon, Ryan Ottley, and 1 other (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #4)

Murf started reading Hack/Slash Omnibus by Stefano Caselli (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #1)

Hack/Slash Omnibus by Stefano Caselli, Dave Crosland, Skottie Young, and 1 other (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #1)

Murf wants to read Hack/Slash Omnibus by Stefano Caselli (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #1)

Hack/Slash Omnibus by Stefano Caselli, Dave Crosland, Skottie Young, and 1 other (Hack/Slash Omnibus, #1)

Murf started reading The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne

The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne

The Mysterious Island tells the tale of five Americans who, in an attempt to escape the Civil War, pilot a …

Murf finished reading Stalingrad by Antony Beevor

Murf wants to read Astronomy by Stefan Deiters

Murf started reading Stalingrad by Antony Beevor

Stalingrad by Antony Beevor

This gripping history is the definitive account of the battle that shifted the tide of World War II, conveying the …